In a world over-saturated with information and misinformation, many artists are turning to more direct modes of communication to expose and reclaim the cultural and political power of words.

‘Do I have to spell it out for you?’ brings together a group of artists incorporating language and text into their work to speak directly to their audience. Through puns, song lyrics, spoken word and personal musings, the artists highlight the complexities of language to create community, define identity and tell stories.

The combined works reveal the potency of language as a means of resistance, cultural artefact, joke, and tool of sovereignty.

This exhibition is presented as a Town Hall Gallery online exhibition from Saturday 5 September - Sunday 25 October 2020. The video works will be available to view for a limited time only.

Featuring: Benjamin Aitken, Chun Yin Rainbow Chan, Kate Just, Nasim Nasr, Claudia Nicholson, Kenny Pittock, Christian Thompson and Shevaun Wright.

Kenny Pittock has also created a fun colour by numbers activity for the school holidays.

Image: Christian THOMPSON, Berceuse (2017), installation view, Ritual Intimacy, Monash University Museum of Art, three-channel digital colour video, sound, duration 5:47, image courtesy of the artist and Messums London; Gallery Marcolini, Forli; Sarah Scout Presents, Melbourne; and Michael Reid Sydney and Berlin. Photography by Andrew Curtis.

Berceuse was commissioned by Monash University Museum of Art (MUMA) for Christian Thompson’s survey exhibition, Ritual Intimacy 2017, which toured extensively throughout Australia in 2017-2018.

Works by the artists

Browse the exhibition by scrolling through the image carousel below.

Kenny Pittock employs the humour of puns and wordplay to playfully draw attention to serious global concerns. His series of life-like ceramic ice-creams evoke a warm nostalgia and longing for an innocent childhood Australian summer. On closer inspection it is apparent some of the ice-creams are sorrowfully melting and the text on the product packaging has been cheekily altered to feature more ominous brand names and flavours. Pittock implores a sense of urgency to take action on climate change before these happy memories melt away completely.

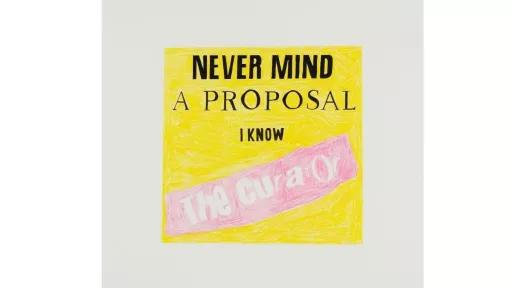

Multi-disciplinary artist Benjamin Aitken injects words and slogans into his paintings and installations as a means of communicating personal narratives, social critique and humour. Many of Aitken’s works are adorned with humorous pop culture references and connotations to communicate more serious social commentaries. More recently, Aitken creates caged ‘shrines’ - installations which draw reference from his experience being baptised as an infant, juxtaposed with consumer products which act as visual metaphors for the artist’s now-secular lifestyle.

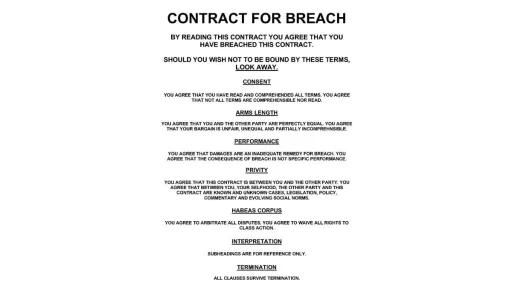

Shevaun Wright uses text in the entirety of her work Contract for Breach, which appears in the form of a legally binding document. The work draws attention to the ways in which words can be manipulated into a tool to both empower and disempower individuals and groups in society.

Claudia Nicholson’s video, All I have are dreams of you (2017), features the artist’s installation of a large alfombra de aserrín (sawdust carpet) dedicated to the late Tejano musician and Latinx icon Selena Quintanilla. Centrally located in the alfombra are lyrics from Quintanilla’s song, Dreaming of you. The lyrics evoke a collective remembering by the Latinx community after Quintanilla’s murder, which was a moment that highlighted the collective force of Latinx political strength in the United States of America. For Nicholson, these lyrics also communicate the sense of longing and distance which she feels towards her birth country, Colombia.

In this three-channel video work, Thompson sings a berceuse – a cradle song or lullaby – as a gesture of re-imagining his traditional Bidjara language, which has been categorised as extinct. The work is premised on the notion that if one word of Bidjara is spoken, or in this case sung, it remains a living language. Combining evocative chanting and electronic elements, Thompson invokes the cultural experiences and narratives of his Bidjara culture.

Chun Yin Rainbow Chan’s video work Triune forms part of the artist’s larger body of research on village women’s oral history and social rituals. The artist spent time with Weitou elders in Hong Kong, including her mother and aunties, to learn about their language, songs and customs. Drawing on her own nostalgic memories of making sweet dumplings with her mother and sisters throughout her childhood, Chan wishes to illuminate the invisible female labour in patriarchal societies.

Nasim Nasr uses script from her native Iran in her art to examine the multiple meanings of words. The Home, The Habit is a series of photographs with the Farsi words manzel (home) and adat (habit) digitally drawn and laser etched into them. The conceptualisation of the series started with a passport photo of two female family members from her grandparents’ 1950s photo album, which had the word manzel handwritten on the back. As the artist explains, ‘this refers to the habit of man, in public, calling his wife - manzel (home), rather than by [her] name.’ Depending on the cultural viewpoint, the use of the word in this context can either be seen as a term of endearment or an act of belittlement and ownership; highlighting how diverse interpretations of language can impact the way culture is viewed and understood.

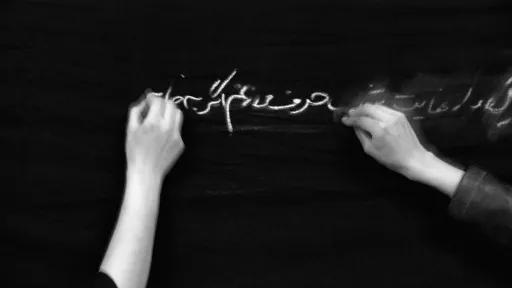

In Erasure Nasr writes in chalk about her own memories, as well as translating text from Iranian feminist poet Forough Farrokhzad and her banned 1959 poem Another Birth. The text is then erased, leaving behind a white smudge, a ghost of past words lingering behind the text of the present.

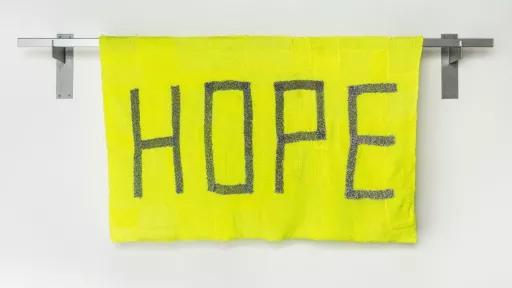

HOPE & SAFE presents the material results of Kate Just’s public banner projects in the UK and Melbourne responding to violence against women and current media coverage of this issue. Referencing and reviving moments in feminist history in which collective action and craftwork were deployed to enact change, HOPE & SAFE invokes a utopian reimagining of women’s safety and agency within the urban environment.

In 2013, Just travelled around the UK with her KNIT HOPE Project. It involved an invitation to individuals and communities to publicly join her in knitting a night-reflective fluorescent yellow banner that spells the word HOPE in silver block letters. Later, various HOPE walks were taken in public at night with it. The HOPE Banner manifests the artist’s wish for a brighter future for women. Materially and conceptually, the banner entwines dualities public and private, individual and collective. The uniquely patterned individual pieces refer to the work of many hands, joined together to form a seamless whole. The durability of the builder’s line and the high-vis reflective material, which is worn by construction workers, police and cyclists, imbues the banner with a level of visibility and authority.

Image courtesy of the artist and Finkelstein Gallery. Collection: Wangaratta Art Gallery.

HOPE Walk Leeds extends on these ideas, documenting a moment in which police on horseback, donning coordinated yellow and silver jackets, asked if they could join the ‘protest.’

On return from the UK in early 2014, Just undertook the KNIT SAFE Project in Melbourne. It involved the communal crafting of a sister banner, a night reflective black and silver ‘blanket’ that spells SAFE. The more sombre SAFE Banner operates as a shield or soft monument constructed in the shadow of recent high profile violent deaths of women in Melbourne including Jill Meagher, Tracey Connelly and Fiona Warzywoda.

Image courtesy of the artist and Finkelstein Gallery. Collection: Wangaratta Art Gallery.

This photograph captures a small group of banner holders quietly interacting with each other in the warm glow of a street lamp, projecting an almost fictional ideal of collective resistance to the harsh realities of the world.